by Deborah McGregor

The ‘research landscape’, internationally and within Canada, has shifted. Emergent Indigenous research approaches continue to shape broader research initiatives. Indigenous research is based on relationships and relationships require work, commitment, energy, communication and continuous engagement; they do not happen just because we want them to.

The importance of creating ethical space for discussion moves the consideration of Indigenous research forward, rather than perpetuating the binary notion of “Western” versus “Indigenous” research. The binary model, while helpful and necessary in distinguishing the key differences, has limited applicability in terms of addressing the rapidly shifting contextual landscape that calls for innovative approaches to Indigenous research practice.

Indigenous research is often viewed as a novel and recently-conceived research paradigm with the aim of explicitly and actively supporting the self-determination goals of Indigenous peoples. While it may be “new” to academia, engaging in Indigenous inquiry, along with its resultant knowledge production and mobilization, is actually far from new. Indigenous societies, like any autonomous and sovereign nations, required regularly updated knowledge to meet existing and emerging challenges. Indigenous peoples have thus been seeking knowledge to support their existence as peoples and nations for millennia

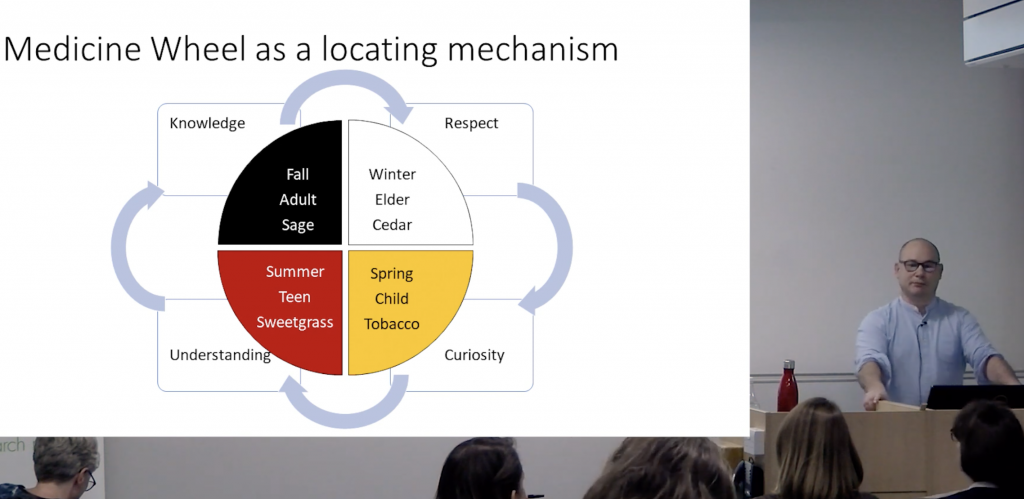

Indigenous societies framed their research through their own ontological and epistemological foundations and methods. Protocols for seeking knowledge were about establishing relationships and have remained so. In such a research paradigm, one shares knowledge and remains accountable to that knowledge, rather than extracting or owning it. Knowledge is grounded in the richly diverse intellectual traditions of Indigenous peoples. This means that there will be a diversity of theoretical frameworks, methods and applications that will reflect the variety of Indigenous traditions.

Moreover, such theories, frameworks and methods are not static: they are continually being revised and continue to evolve. One is not required to “separate” oneself from the research, but to approach it holistically, with the intellectual, emotional, spiritual and physical aspects of the whole self.

Indigenous modes of inquiry have been undermined, deemed inferior (if recognized at all), and even erased through imperial and colonial practices.

In her book, Research for Indigenous Survival: Indigenous Research Methodologies in the Behavioural Sciences, Abenaki scholar Lori Lambert observes that if one is not from the community or nation one is engaged with in research (Indigenous or non-), one can never truly understand the stories being told. Researchers in this sense must be open, honest and transparent about their own limitations with themselves and the communities with which they are working.

In this light, the researcher’s goal is not to tell the community’s story, but to empower the community to tell their own story, on their own terms, their own purpose. Self-determination in research means that, ultimately, communities will determine who they participate with in research, and what methods will be employed. Indigenous scholars have advanced Indigenous research theories and methodologies based on their own cultural foundations, full acceptance of Indigenous research paradigms within the academy remains elusive.

One of the barriers to such acceptance is that “unlearning” of Western modes of research seems to be a prerequisite for embracing Indigenous research.

Rights of Indigenous Peoples

The application of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in research contexts has yet to be fully explored, although it can be argued that any research involving Indigenous peoples should support Indigenous peoples’ pursuit of self-determination. Article 31(1) of UNDRIP has specific implications for Indigenous research:

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and tradition- al cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.

Article 31 (1) UNDRIP

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect, and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports, traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions. (UNGA, 2007)

The concept of negotiating between different knowledge systems is an important aspect of Indigenous research. Indigenous peoples are not rejecting western knowledge systems outright, but are seeking equitable consideration and application of both systems when and where appropriate. There is no single Indigenous research paradigm approach. Indigenous research is as diverse at the peoples who engage in the process.

Anishinabek research

The Anishinabek have been actively seeking assistance and knowledge since time immemorial; research for us is therefore not a novel experience. University-based Anishinaabe researchers also seek Minobimaadizwin (good life) as an outcome of their research, although different methods may be used to achieve this goal. Anishinabek research is a form of reclaiming our stories and knowledge through personal transformation while in the pursuit of knowledge. As Anishinaabek, we have our own worldviews, philosophies, ways of being, and research traditions that account for our relationships and existence in the world. Anishinabek transforms and represents a diversity of ways in which Anishinabek are tackling the challenging, yet transformative, work involved in re-creating our knowledge on our own terms.

Anishinabek research is a form of reclaiming our stories and knowledge through personal transformation while in the pursuit of knowledge. As Anishinabek, we have our own worldviews, philosophies, ways of being, and research traditions that account for our relationships and existence in the world.

The Anishinabek researcher’s preoccupation is to learn to engage appropriately in a series of relationships with other beings in Creation to serve our nations now and into the future.

Ethical research protocol requires that respect be given to those who have shaped and contributed to our knowledge (community, familial, and personal knowledge) and have greatly influence the approach that we take to research. For the Anishinabek, cultural protocols require us to acknowledge our personal knowledge sources, just as we would cite sources from the scholarly literature.

Ethically, we work to recognize and livethese relationships. In an Indigenous research paradigm, our ethics or conduct always includes the environment (or all of Creation), as well as the spirit world, no matter what the research questions or topic. In Anishinabek research paradigms, our original sources of information are our ancestors, who were real people living their everyday lives, as well as the places that we come from.

Wendy Geniusz, Cree scholar refers to this view of Anishinabek research as biskaabiiyang,or “returning to ourselves”. As Anishinabek, we must engage processes of decolonizing at many levels so as to reclaim, recover and revitalize Anishinabek intellectual, spiritual and ethical traditions, or Anishinaabek-gikendaasowin (knowledge).

Anishinabek people have always sought knowledge in systematic ways, engaging in protocols that included the proper ethics and conduct for doing so. This is not new. Knowledge is a gift to share for the well-being of the people and is acknowledged by other Anishinaabe scholars as the pursuit of Minobimaadizwin or “the good life”.